Ashley Hurst of Osborne Clarke LLP is appealing against the decision of the Solicitor’s Disciplinary Tribunal that Hurst improperly attempted to restrict a tax lawyer from publishing correspondence revealing he was being threatened with legal action in relation to his scrutiny of Nadhim Zahawi’s tax affairs.

The decision was handed down in December 2024 and was the first case brought by the Solicitors Regulation Authority (SRA) in response to concerns about lawyers engaging in Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation (SLAPPs).

A victory in all but name?

While the Tribunal agreed with the SRA that Hurst had engaged in professional misconduct, its written judgment concluded – without setting out clear reasons – that the case was “not a SLAPPs case”. This exposes a troubling lack of understanding by the Tribunal about the way that abusive legal tactics work to stifle public scrutiny and highlights a fundamental misalignment between the SRA and the Tribunal on the topic of SLAPPs.

Hurst’s appeal against the Tribunal’s ruling, set down for hearing on 27 November 2025, gives the High Court an opportunity to weigh in on fundamental questions about the role of lawyers in a case arising out of a SLAPPs complaint.

Background

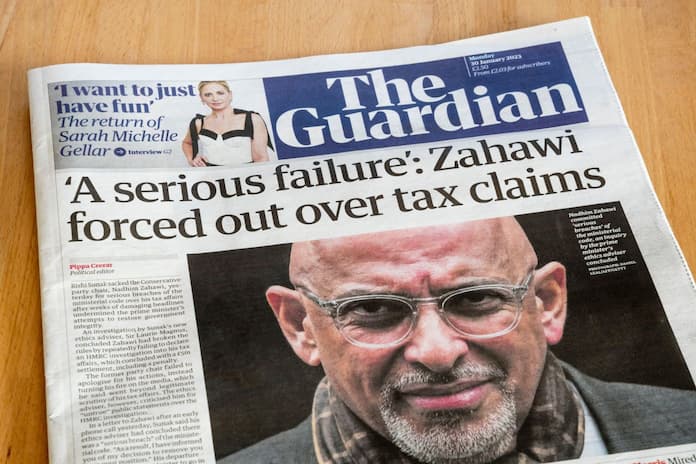

The case concerned correspondence sent by Hurst to Dan Neidle of Tax Policy Associates in 2022 when Hurst was acting for Nadhim Zahawi, who was then Chancellor of the Exchequer and a candidate in the Conservative Party leadership campaign.

The legal correspondence was issued because Neidle had published various articles and posts on his website commenting on Zahawi’s tax affairs and accusing him of lying in relation to the use of offshore companies. Hurst emailed Neidle asking him to retract his allegations of lying against Zahawi.

Neidle originally referred Osborne Clarke to the SRA in 2022 claiming the law firm had been complicit in misleading him about Zahawi’s tax affairs. Instead of pursuing this more serious allegation of dishonesty, however, the SRA’s case before the Tribunal focused on the much narrower issue of the appropriate labelling and content of legal correspondence issued by Mr Hurst.

Hurst marked his email ‘without prejudice’ – a label indicating the communication is made in a genuine attempt to settle a dispute and so is protected from disclosure in court as evidence of admissions against the interests of his client. The email from Hurst also stated that “you are not entitled to publish … [this email] … or refer to it other than for the purposes of seeking legal advice. That would be a serious matter, as you know. We recommend that you seek advice from libel [sic] lawyer if you have not done already.”

The Tribunal was asked to consider whether Hurst’s correspondence “improperly attempted to restrict Neidle’s right to publish that correspondence and/or discuss its contents”, and whether in doing so it breached the SRA’s Code of Conduct and Principles.

The Tribunal found Hurst did commit professional misconduct by applying ‘without prejudice’ labelling to correspondence which contained no genuine attempt at negotiation or resolution, and also by using wording that attempted to prevent Neidle from disclosing either the email or its contents to anyone other than a legal adviser.

The Tribunal imposed a £50,000 fine against Hurst for his professional misconduct and ordered him to pay the SRA’s costs of £260,000.

Despite this successful outcome for the SRA, the Tribunal stated in the course of its judgment that “this was not a SLAPPs case”.

Why this case matters

- This was the first case of its kind against an English solicitor accused of engaging in abusive legal tactics to shut down scrutiny of his client. After growing concern about the use of SLAPPs to silence the critics of wealthy and powerful clients, the SRA has shown encouraging appetite to respond to complaints about lawyers who allow themselves to be used as guns for hire in this way.

- While the SRA was successful in making out its case that Hurst breached his ethical duties as a solicitor – relying on its SLAPP guidance to do so – the Tribunal made the unsolicited and troubling finding that this was “not a SLAPPs case”. This shows a lack of understanding about how SLAPPs operate to intimidate and silence critics, and is out of step with the SRA’s expectations and guidance as the solicitors’ regulator about what SLAPPs, as a form of professional misconduct, involves.

- The case is a key test of how the rules of professional ethics that bind solicitors are applied to assess complaints about SLAPPs. In building its case, the SRA relied on its March 2022 Guidance on Conduct in Disputes and the principles set out in its later Warning Notice on SLAPPs. The Tribunal’s task was to assess whether Hurst breached the SRA Principles or Code of Conduct, not to make its own determination of whether a case constitutes a SLAPP. Yet in going out of its way to weigh in on whether the case fell into the category of a SLAPP, the Tribunal has muddied the waters about how SLAPPs fit within the framework of professional ethics.

“Not a SLAPPs case”?

In its case against Hurst, the SRA put forward arguments that drew upon its March 2022 Guidance on Conduct in Disputes. In particular, the SRA took issue with “the attempt to limit or restrict Mr Neidle’s ability to comment publicly on the correspondence he had received from a solicitor acting on behalf of the-then Chancellor of the Exchequer” and the “improper attempt to limit or restrict Mr Neidle’s ability to publish or discuss” the correspondence. The solicitors’ watchdog maintained that this oppressive and intimidating approach had been condemned by the SRA in its March 2022 Guidance.

Although the facts in this case arose before November 2022 when the SRA issued its first Warning Notice on SLAPPs (which made clear the kind of SLAPPs conduct that is prohibited), the SRA clearly relied on the principles set out in its Warning Notice on SLAPPs in formulating its complaint and criticising Hurst’s conduct.

The SRA also claimed that the correspondence issued by Hurst contained an “implicit threat of serious consequences” should Neidle disclose the contents of the correspondence or even the fact of Hurst’s attempted prohibition on disclosure.

The Tribunal agreed with the SRA that the email issued by Hurst carried an implicit threat of legal action if Neidle disclosed the email or the fact of the claim, and that Mr Hurst’s attempt to restrict Neidle’s right to publication of the email was improper.

While siding with the SRA on the merits of its case, however, the Tribunal made a point of stating that this was not a SLAPPs case. This, arguably, fails to grasp the heart of concerns about SLAPPs. By their very definition, SLAPPs “are a misuse of the legal system, through bringing or threatening claims that are unmeritorious or characterised by abusive tactics, in order to stifle lawful scrutiny and publication, including on matters of corruption or wrongdoing.“

As events have transpired, it is now clear that Zahawi had failed to pay proper tax and reached a £5 million settlement with HMRC which included the payment of a penalty.

Zahawi knew that HMRC were looking into his tax affairs yet failed to disclose this and was ultimately sacked by the Prime Minister as Tory Party Chairman and lost his Cabinet position over it. His sacking followed criticism by the Prime Minister’s ethics advisor Sir Laurie Magnus about Zahawi’s characterisation of media scrutiny as “smears” and his “delay in correcting an untrue public statement”.

Even on the terms of the Tribunal’s own findings, Hurst’s acted improperly in using wording that sought to prevent the disclosure of his threatening email which sought the retraction of what Neidle had published about Zahawi as part of Neidle’s lawful scrutiny of the Chancellor’s tax affairs. So what reasons did the Tribunal give to justify its assertion that this was not a SLAPPs case?

While not setting out clear reasons for making this determination, the Tribunal commented that “this was not an attempt to obstruct scrutiny of Mr Zahawi’s tax affairs. Rather, the intention was to narrow the focus of the dispute to Mr Neidle’s allegation of dishonesty.”

Not only did the Tribunal not give sufficiently clear reasons for its assertion that this was not a SLAPPs case, but it did not provide any clear written explanation as to how the Tribunal defined a SLAPP. Based on comments by the panel during the hearing, the Tribunal appears to have considered that Hurst’s conduct did not attempt to prevent scrutiny of the Chancellor’s tax affairs because this material about Zahawi was already in the public domain at the time of the correspondence.

This fundamentally misunderstands how SLAPPs operate to stifle public scrutiny, restrict publication and intimidate targets into silence. The attempt to prevent publication of the correspondence is inextricably linked to what that correspondence was seeking to achieve – namely, the retraction of what Neidle had written about Zahawi’s explanations to the press and public in the course of scrutinising his tax affairs. One cannot artificially separate Neidle’s scrutiny of Zahawi’s tax affairs from his views about what that scrutiny revealed.

While it is true that material concerning Zahawi’s tax affairs was in the public domain and was already being scrutinised by the public and the media, this does not preclude the possibility that Hurst’s aim in attempting to prevent Neidle from publishing the email was in fact precisely to prevent further public scrutiny of his client’s tax affairs within the context of a serious allegation of dishonesty. The Tribunal failed to acknowledge this vital aspect of Hurst’s threats against Neidle.

The content of the email was a matter of public interest, as was Zahawi’s efforts, as an individual holding high public office, to keep the contents of the email secret. In the words of the SRA, “the public would have wanted to know that Mr Zahawi was resorting to legal letters in an apparent attempt to limit Mr Neidle’s commenting on his tax affairs, and was seeking to keep that fact from public scrutiny.”

The Tribunal was not asked by the SRA to determine whether this complaint should be classified as a SLAPPs case. The Tribunal’s task was rather to assess whether Hurst’s conduct fell short of his professional ethical duties as set out in the SRA Principles and Code of Conduct. The Tribunal’s conclusion in the context of its limited discussion on SLAPPs that Hurst was not motivated by any improper intent is also difficult to square with its finding that Hurst’s intention was indeed to prohibit publication of the correspondence.

The confusion left by the Tribunal’s statement on SLAPPs

As a regulator, the SRA has been actively seeking to set guidance in the context of concerns about the role of lawyers in bringing SLAPPs. In formulating its case against Hurst, the SRA placed strong reliance on its March 2022 Guidance and the fundamental concepts and principles contained in its Warning Notice on SLAPPs which clearly signal its expectations as a regulator about the professional obligations of solicitors and law firms.

The Tribunal sided with the SRA in finding that Hurst had used legal tactics (the ‘without prejudice’ labelling and the “implicit threat” of legal action), to improperly restrict disclosure and deter publication. However, the Tribunal’s approach in not only declining to label such conduct a SLAPP, but to emphatically state that the behaviour was not a SLAPP, exhibits a lack of understanding about the operation and effect of abusive legal tactics on its victims and the public interest.

The Tribunal’s approach is also damaging to the broader attempt to stamp out abusive legal tactics. The troubling lack of clear reasoning behind the Tribunal’s statement that this case was not a SLAPP sends a confusing message to the legal profession regarding regulatory tolerance of abusive conduct in proceedings and also discourages potential SLAPPs complainants coming forward to the legal regulator.

One of the most insidious aspects of successful SLAPPs is that they stop vital information of public interest from entering the public domain. This may include suppressing the public disclosure of the actual legal tactics that are used to effect the SLAPP. In this case, Hurst sought not only a withdrawal of Neidle’s allegations of dishonesty against his client (i.e to expunge vital public interest information from the public record), but he also sought, in sending a without prejudice email prohibiting disclosure of the email itself, to prohibit Mr Neidle from publishing details of the tactics and threats that Hurst was using in seeking to effect such suppression.

Widely regarded as the first test case for how regulators approach concerns about SLAPPs, it is disappointing that the Tribunal’s judgment confuses rather than clarifies how professional ethics relate to SLAPPs.

Hurst’s appeal to the High Court argues that the Tribunal’s findings against him are “irrational and unsustainable”. While Hurst’s appeal will challenge the approach taken by the Tribunal to his use of labels, it will also offer an important opportunity for the SRA – and the High Court – to clarify the professional misconduct at the heart of concerns about how SLAPPs seek to stifle publication of information in the public interest.

The need for comprehensive Anti-SLAPP legislation alongside robust regulatory action

The Tribunal missed an opportunity in this early test case to send a clear signal to the profession about the professional misconduct which is at the crux of abusive and oppressive legal tactics, and has instead created confusion about the identification of SLAPPs.

In addition, the SRA’s efforts to set clear expectations for the legal profession are not helped by the absence of comprehensive legislation against SLAPPs. So far, the government has only legislated against SLAPPs in the context of economic crime, and the SRA itself has called for “a robust legislative solution” concerning SLAPPs as “the principal way to reduce opportunities and incentives for claimants to abuse the system”.

In the absence of a clear and comprehensive anti-SLAPPs law, together with a regulatory environment that effectively prohibits the deployment of abusive legal tactics to stifle lawful public debate and scrutiny, concern remains that lawyers will continue to improperly use such tactics in pursuing their clients’ interests.

Tribunal documents

Solicitors Regulation Authority Ltd v Ashley Simon Hurst – judgment of the Solicitors Disciplinary Tribunal dated 14 May 2025

High Court documents

Ashley Simon Hurst v Solicitors Regulation Authority Ltd – Applicant’s grounds of appeal

Ashley Simon Hurst v Solicitors Regulation Authority Ltd – Respondent’s notice