With just hours to go before Parliament went on recess, the government last week snuck out its long awaited (and very overdue) response to three separate independent reports on strengthening ethics and integrity in central government.

It’s worth reflecting on why this response is so important. Trust in government is crucial for the strength of democracy but it is at record lows. Poll after poll shows that the majority of the UK public think politicians are among the least trustworthy of all professions and are angry at politicians for lack of honesty and integrity. By large margins they support much stronger, more independent regulation of politicians and those in government.

There is also a growing view among constitutional experts that the current ‘good chaps’ theory of regulating politicians is broken and needs to be replaced by harder-edged rules, properly enforced. The lessons of populism, whether in the UK or in other countries, is that those who get into power cannot always be relied upon to be ‘good chaps’, leaving our democratic institutions vulnerable.

So a robust response to three independent reports calling for major upgrades to how ethics is regulated was in order, not least to show that the current Prime Minister’s much highlighted pledge to lead a government with integrity, professionalism and accountability, would be backed by action not just words.

The reports could not come from more credible sources: one from the independent Committee on Standards in Public Life (CSPL), which advises the Prime Minister; an independent review by Sir Nigel Boardman commissioned by the government in the wake of the Greensill scandal; and the UK Parliament’s Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee.

And between them there was considerable consensus on the need for reform, focused around four key areas:

- Regulation of ethical standards in government, including of ministers

- Regulation of the revolving door between government and business

- Ensuring public appointments are made fairly to avoid cronyism, and

- Transparency in lobbying.

Following in the footsteps of our ‘Integrity Deferred?’ report from March, the Spotlight team has combed through the government’s response to assess which of the reports’ recommendations have been implemented and which got short shrift. Below is our overview, with detailed analysis behind these conclusions here. CSPL did their own assessment of this for their recommendations, as has the Institute for Government. In a few areas, we’ve taken a slightly different view, where we think the government substantively rejected a recommendation and their alternative proposal did not amount to even partial implementation.

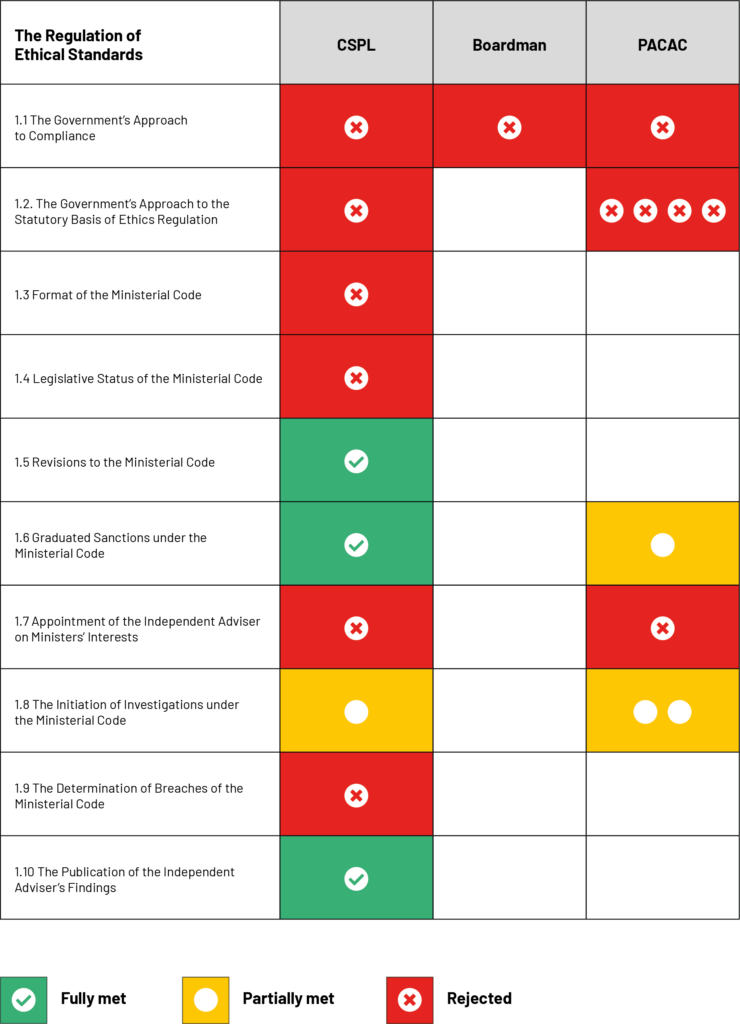

Regulation of ethical standards

This is the area where the government implemented the least – in fact, there was nothing new in here at all. The government rejected giving any stronger independence for ethics regulators, including the Independent Advisor on Ministers’ Interests. Where the government had accepted some tweaks in the Independent Advisor’s role, these had already been done some time ago.

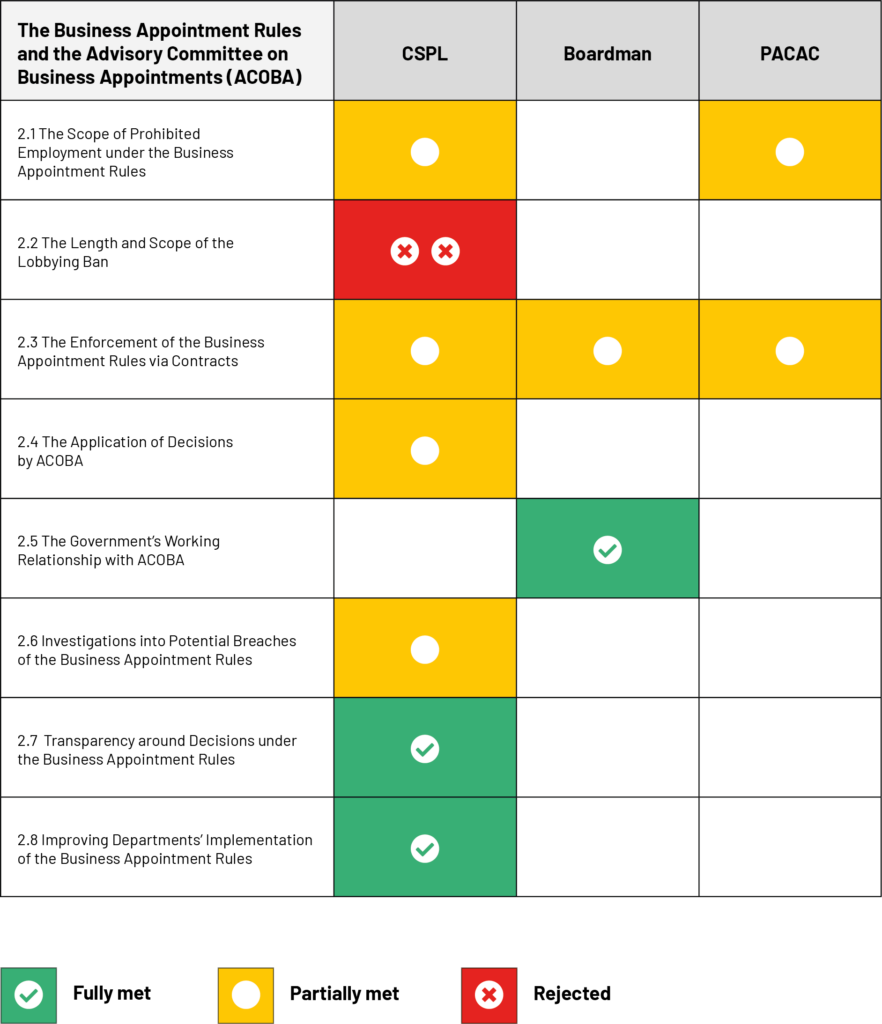

Regulation of the revolving door

Here, the government’s eye-catching new contractual arrangements for civil servants and ministerial deeds, look promising as a headline. However, overall just three out of eight areas for reform have been fully implemented and there are some serious outstanding questions about how these will be enforced and by whom. In particular, it’s not clear how the new contractual arrangement will be enforced. For example, while Lord Pickles is (rightly in our view) calling for financial penalties for breaches of revolving door rules, the government’s response suggests it will “explore” this “if needed,” which suggests we’re some way away from that becoming reality.

Ensuring public appointments are made fairly

On this issue, the government did better – with recommendations in four out of the seven areas being broadly accepted. That included reforming how Non-Executive Directors of government departments are appointed – a widely recognised high-risk area –- and greater transparency when ministers appoint people directly. However, the big ‘no’ in this area was making sure the appointment of the ethics regulators themselves was more rigorous, which, given public demand for more strongly independent regulation of standards for ministers, is concerning.

Transparency in lobbying

This is the area where the government made its seemingly boldest moves. A new database to be created, updated monthly, with better descriptions of what was talked about, and meetings with senior civil servants included. What’s not to like?

However, the devil is in the detail (and in the recommendations that the government rejected). Most glaringly, special advisors are exempt. Everyone from CSPL, to Boardman to the Registrar of Consultant Lobbyists has recognised the crucial role that special advisors play in terms of access to decision-makers – so this is a major loophole.

Meanwhile, there’ll be no way of penalising departments that fail to file the right information on time, because the government rejected any accountability mechanism. And widening the register of consultant lobbyists to address loopholes or having some enforceable behaviour rules for lobbyists was ruled out completely.

Conclusion

As Lord Evans, chair of the CSPL, put it, “some repairs have been done” to the way ethics are regulated for ministers and top senior civil servants. But that is a long way from the major upgrade that the slate of recent sleaze scandals and declining public trust clearly seems to merit.

Meanwhile, Lord Pickles, current chair of the Advisory Council on Business Appointments (ACOBA) – the revolving door regulator – has rightly been calling for some proper deadlines by which the government will implement these measures. After waiting for two years for these reforms, the plan was disappointingly published with no timetable at all.

Overall, the government has opted in its reforms to improve transparency without increasing accountability for how politicians behave. The real risk with that approach is that many people’s view that the current system is rotten, with special interests getting special access will be confirmed, as will the widely held view that politicians get to play by a different set of rules and with few consequences for bad behaviour.